Brother, Teach Me

A hero’s journey to find the meaning of heroism.

I’ve spent the last several years trying to figure out how to be a man. On the whole, the experience has been frustrating, and progress slow. But, finally, I think it’s clicked.

It’s a bad time to be a bloke. What was in vogue for millennia is now old hat. I think it’s fair to say that we men aren’t taking this with much grace, as evidenced by the current Types of Guy one can elect to be. Firstly there’s the gooners (Mum, don’t click on that link), the groypers and of course the other branches of the Manosphere genus, the phylogeny of which is more than adequately covered elsewhere. There are the adherents to the three Bs - beers, babes and ‘ball - whose seeming obliviousness to our collective lechery perpetuates the nation’s most socially acceptable form of voyeurism, Love Island. There are the Finance, Tech, and, regrettably, FinTech Bros, whose blood is running money. There are roadmen and wastemen, middlemen and gyal men, madmen and sad men.

Then there’s the ToG I am, an acolyte of Bo Burnham and David Foster Wallace1, a particularly neurotic amplification of the already caricaturesque softboi. We desperately hope that wrapping ourselves in enough layers of self-awareness2 will excuse us of any wrongdoings, when in reality the terminal state of our archetype more likely resembles Worst Boyfriend Ever (Not for you either Mumsy, sorry!) than saintly redemption. This isn’t really a model for masculinity as much as it’s a rejection of it. It’s an attempt to distance ourselves from the sins of our gender, to purify ourselves in the court of public opinion by rejecting any possible association with the villainous, brutish Alphas. Ultimately though, it is lazy, even cowardly; despite its violent defenestration of outdated ideals of manhood, it fails to present a viable alternative.

And, honestly, it sucks. I’ve often felt a twinge of jealousy when realising how many of my female friends are proud to be women, and keep this as a central pillar of their identity. When considering my manliness, I’ve felt apathy at best, and shame at worst. I cringe at the myriad stories of men doing awful things. I feel embarrassed that despite having the advantage of maleness in my education and career, I’ve still chronically failed to live up to my potential. My gender’s role in my psyche is largely as fodder for my rampant proclivity for interior self-flagellation. Undoubtedly this is strychnine for the soul.

Spoilers ahead for Friendship and RRR.

Recently I watched the A24 film Friendship along with some, uhh, friends. It features prime and unenviable examples of two different ToGs, as well as their equally unenviable friendship. Craig (Tim Robinson) is overtly a pathetic loser who tries to befriend Austin (Paul Rudd) who is covertly a pathetic loser. The entire film is shot-after-shot of their craven, performative, emotionally unintelligent attempts at male bonding. While satirical, it hit painfully close to home to watch this bumbling anti-bromance careen awkwardly across my screen. I’ve always found it difficult to be vulnerable with men - I don’t think I’ve ever cried in front of any of my male friends (at least not sober), and still feel awkward hugging them. There still remains some ego, some sense of competition, some feeling that I cannot let my guard down with this person, and this vigilance is mutual.

The next night, I managed to cajole everyone into watching perhaps my favourite film ever, Tollywood’s RRR, as an antidote of sorts. I’ve seen it several times, and had often thought a large part of the appeal was its depiction of the bond between the twin protagonists - a non-genetic fraternity so strong that it single-handedly vanquishes the British Raj! Being the dirty slut for intimacy that I am, I too want such connection. I even joked that the male-male friendships I want are those depicted in RRR, while the male-male friendships I actually have are those depicted in Friendship.

RRR features the dual heroes’ journeys of Ram (Ram Charan) and Bheem (N. T. Rama Rao Jr.), which eventually combine into a kind of mega-monomyth. They begin as superficial allies, before betraying one another in pursuit of their own higher goals, and only then realising that pursuing one’s goals at the expense of one’s friends is a failure of its own. Upon their re-unification, their combined might is such that they not only fulfil both their individual objectives, but strike a devastating blow to their oppressors and incite the revolt that will eventually drive the British from India. Along the way they fight tigers, leap from burning buildings, rescue damsels in distress, destroy punching bags by fisticuffing them too hard, spend time in solitary confinement doing pull-ups, and refuse to kneel during a vicious flogging. They also sing heartfelt ballads (including during the aforementioned flogging), dance, cry and show great vulnerability with one another.

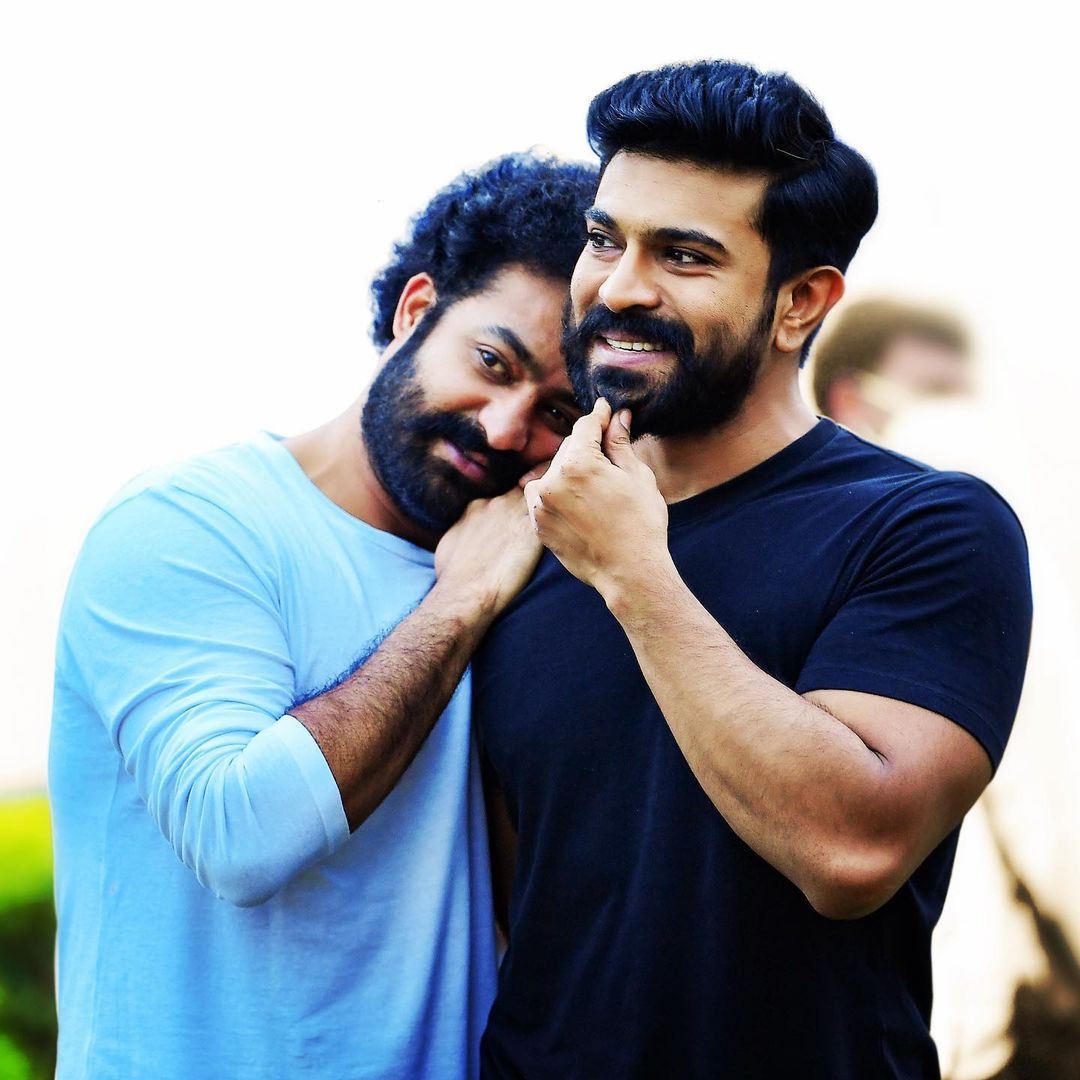

This time around, I finally realised that it’s the bros that beget the bromance. The reason Ram and Bheem have such an extraordinary relationship is that they are both extraordinary men in their own right. Part of my love of the film invariably comes from my general ignorance of Indian cinema; to Western audiences it seems over-the-top, camp, and unrealistic, whereas to me it is so earnest and unashamed that it makes every Hollywood movie I’ve seen cowardly in comparison3. This extends to the characters; there aren’t figures like Ram or Bheem in Western culture, whether fictional or otherwise. They are strong, brave, loyal, protectors of the weak who will go to great lengths and willingly sacrifice themselves in order to serve their community. The fact that they dance, cry, and display great gentleness and humility only augments their masculinity. The closing dialogue - “how can I repay you?” “brother, teach me” - is sheer perfection. They’re even affectionate offscreen!

While I don’t want to be like DFW, he was right about many things, including his assertion that sincerity is sorely underrated and that irony is tantamount to cowardice. This realisation didn’t absolve him as he’d hoped, and so he cowered behind self-awareness and the shadow of the bottle instead. Like many others, he only showed me one of many flavours of manliness to avoid, while offering no desirable substitute. I’ve searched in vain for years to find a suitable replacement for my abandoned male archetype, before finding it in the most unlikely of places - a film, over three hours long, in a language I don’t know a single word of, from a culture that I understand embarrassingly little about, that contains such unparalleled maximalism it ought to have been maximally offensive to my restrained British sensibilities.

Today, I vow to work to become this kind of man - one who has a sense of honour and bravery while also cultivating gentleness and vulnerability. One who fights for what he believes in when duty calls, and sings and dances without shame when it doesn’t. One who throws off the shackles of irony, and lives life full-heartedly. One who takes Ram and Bheem as his guides.

-

As you can see, this extends to aping DFW’s written tics. ↩︎

-

I’m doing it even now; I can’t help myself. I am trapped in this never-ending cycle of ironic self-reference, unable to escape - please help me! ↩︎

-

The film is also a great scissor for whether communication should be about facts/truth/reality or about emotions/community/vibes. I am firmly in the latter camp. ↩︎